BLOG

IoT Product Compliance Guide, Part 2: What Devices Need Certification?

In part one of this guide, we talked about why product certification matters for IoT and the different regulators and certifications that you need to know about. Now, we’ll dive into a discussion about the kinds of devices that need to be certified. In Part 3, we’ll explore the costs and the actual process of achieving IoT product compliance.

**The information provided on this blog post does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice; instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Readers of this blog post should contact their attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular legal matter.

Which Devices Need to be Certified?

We know that product certification needs to happen. We know which regulators control which kinds of tests/standards. So, what kinds of devices and products do the rules apply to? Technology has evolved significantly in the past few decades and the same kinds of certification rules that would have been applied only to a camcorder in the 1980s can now also be applied to your mobile device. In addition to a video recorder, it is also a camera for still photos, and a computer, and a cellular phone, and a navigation device, and a flashlight, and a lot of other things.

Here’s a list of the kinds of information technology devices you’ll need to certify with one or more of the regulators we looked at in Part 1 of our guide, depending on where you plan to manufacture and market the product. Note that just one product could include multiple categories, so it might also be helpful to modularize each component during the design process to make it easier to test:

- Any electronic product that operates at frequencies 9 kHz or higher (FCC & IC)

- Any product connecting to the alternating current (AC) power grid

- Most intentional radiators (includes the majority of IoT devices)

- Cellular devices

- Bluetooth devices

- Wi-Fi devices

- ZigBee radios

- WLAN

- LoRA (Long Range)

Types of RF Devices

There are five types of RF devices governed by the FCC. The complexity and amount of testing required are primarily dependent on the type of RF device.

Low Test Effort

Incidental radiators (non-digital devices) and unintentional radiators (digital devices) are common in day-to-day life. They are things like air conditioners and alarm clocks, respectively. The tests for these products generally take less time. Interestingly, neither of these types of devices contains a radio transmitter, but they can ultimately emit a fair amount of RF noise if not properly designed.

High Test Effort

Going to the other end of the spectrum in terms of testing complexity are Industrial, Science, and Medical (ISM) band transmitters that operate in several different bands. The most common are 902 – 928 MHz (LoRa), 2.4 GHz (Wi-Fi and Bluetooth), and 5 GHz (Wi-Fi). These are typically low-power devices that transmit less than a single watt of power, and they are required to frequency hop within their respective band. These are sometimes referred to as unlicensed transmitters.

The most complicated in terms of compliance testing are licensed transmitters such as cellular technology. The ISM and licensed transmitters are commonly put on a pre-certified module that is then included in large assemblies, but that does not always have to be the case. Most IoT devices will be unlikely to fall into this classification.

IoT Devices

In the IoT space, almost everything has a radio and is considered an intentional radiator. If the product has a single radio that is pre-certified, then the testing is relatively easy. If the product contains more than one radio, however, things become a little more difficult – even with pre-certified modules – and particularly if there are collocated transmitters. This is only an issue if the two (or more) antennas are within 20 cm of one another. Alternatively, if you can guarantee that the two radios will never transmit simultaneously, then this requirement is laxer. Lastly, depending on the type of radio module utilized, entire sets of testing can be avoided.

Device Classes

All RF devices can be grouped into either class A or class B devices. Class A devices are intended for use in industrial or business applications. Class B devices are intended for use in residential or personal applications. This does not have a major impact on the tests required but it does change the allowed energy levels in a few frequency bands. The device class will also impact some verbiage required in your documentation and on labels.

Pre-Certified Components

It’s true that you can expedite or even avoid some certification tests of your finished product if you use pre-certified parts (like an end-certified cellular module). It’s critical to note, however, that using a pre-certified device for your product doesn’t guarantee that it will pass or even skip a compliance test. (I know – this flummoxed me at first, too.)

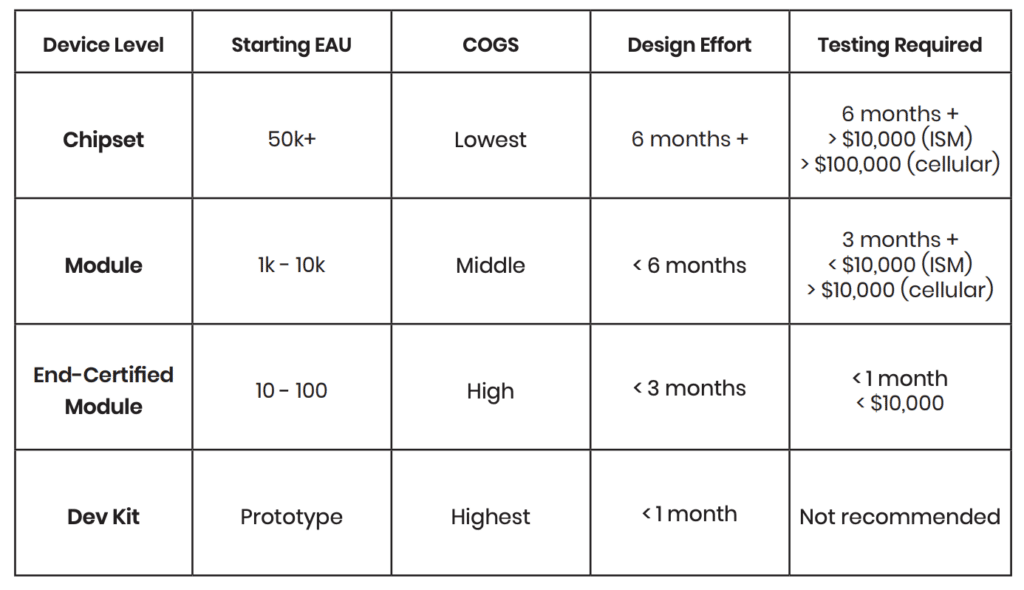

There are four levels, so to speak, of pre-certified radios that are “put down” on a device. In order to choose the right solution for your product, you should ask yourself three things:

- What is my anticipated annual production volume?

- What is the cost of goods sold (COGS) target?

- How quickly does it need to get to market?

While actual product certification requirements will be much more nuanced than the information provided below, it helps to have a general understanding of how these three questions ultimately will impact radio device selection.

Note: the manufacturers and components listed below are not endorsements, but examples.

- Chipset: This solution requires the selection of the integrated circuit (IC) itself along with all the required supporting circuitry.

- Qualcomm is perhaps the best-known manufacturer of cellular chipsets.

- Texas Instruments provides several chipsets for ISM applications with their CC series.

- Module(often called a pre-certified module): Modules that require a host circuit board.

- Contains an RF chipset plus other components.

- If power were applied only to the module itself, it would be unable to operate.

- May require an external RF connector, SIM card, and/or other minimal circuitry.

- Cellular module manufacturers include Telit, U-Blox, and Sierra Wireless.

- Microchip provides several WiFi and/or Bluetooth modules.

- The end-product must go through additional testing because it is an intentional radiator.

- End-Certified Module: These are typically devices that are pluggable via standard connectors or they are soldered onto a host PCB.

- Essentially, it is a module, but it adds in the external antenna/RF path (perhaps an interface controller) and, for cellular, the SIM card.

- If powered, they could operate on some minimalistic level, if not fully.

- Companies like Digi have both cellular and ISM offerings.

- Multitech and Nimbelink also have cellular end-certified modules.

- The end-product must go through basic FCC and UL testing because it contains an intentional radiator that has been independently approved.

- “Inherits” the module certification.

- Dev-Kit: Essentially an end-certified module.

- Can typically plug into a USB connector or other common household style of connector.

- Primarily suited for prototype and proof-of-concept deployments.

It is important to note that, more often than not, devices including ISM technologies are going to be fairly straightforward as far as compliance testing is concerned. For end-products utilizing a cellular connection, however, there may be carrier testing, in addition to FCC and UL testing, required if not using an end-certified module.

For a module, the radio itself may have been certified, however, your device is almost certainly using it in a new configuration, may use a different PCB material, or it is used in conjunction with another product that alters the radio’s performance. However, on an end-certified module, the relationship between the various components of the radio is fixed, and the material of the PCB is guaranteed not to change. There is also generally a controller on an end-certified module that takes commands from the host processor and then interfaces with the RF chipset.

Putting Your Product Certification Knowledge Into Action

Now that you know why you should care about IoT product compliance, who the major players are in the space, and how these rules apply to your device, how do you get started certifying your product?

In Part 3 of this guide, we will review the costs and the process for product certification so that you can approach your next product release with confidence.